Japanese architecture's days of future past

2011/10/16

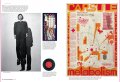

The DNA double helix-shaped project created by Kisho Kurokawa, foreground, and computer-enhanced images of Arata Isozaki's tree-like structures draw the attention of visitors to an exhibition on the Metabolism movement. (The Asahi Shimbun)

In a country that lies on the volatile Pacific Ring of Fire, designing buildings that can withstand earthquakes has always topped the list of priorities for Japanese architects.

Yet, although most structures near the northeast coastline of Japan withstood the violent rumblings of the Great East Japan Earthquake, many did not survive the devastating power of the subsequent tsunami. As people wonder what would happen if a similarly large wave hit again, faith in Japan's model for urban planning and construction has been deeply shaken.

The architects in charge of reconstructing the Tohoku region must now not only plan disaster-resistant and energy-efficient settlements, but also find a way to serve the needs of the existing community as well as enticing others to move in and revitalize what was already an ailing region.

To do so, they might find some inspiration in the Metabolism school of architecture, which emerged during Japan's last large-scale reconstruction project in the postwar period. The movement is currently being explored in an exhibition at the Mori Art Museum in Roppongi, Tokyo, through Jan. 15.

Like the architects currently working on projects in Tohoku, the Metabolists were faced with the challenge of rebuilding from scratch. They determined that traditional urban models, comprised of clusters of discrete buildings, were not up to the task. Instead, they envisioned self-regulatory, cooperative and integrated structures that functioned like an ant colony or cells and organic systems of the human body.

According to architecture critic Noboru Kawazoe, the central members of the movement--which included Kenzo Tange, Kisho Kurokawa and Kiyonori Kikutake--believed that buildings and settlements should grow and adapt to their environment, letting the old be replaced by the new. In nature this process is known as "metabolism," hence the name of the movement.

"Life forms are different from everything else because they keep growing as they are replaced," Kawazoe said. "Humans are just another life form on earth--and the cities we build are just the same as anthills."

Taking their inspiration from cells, honeycombs and fractals, the Metabolists produced dazzlingly futuristic designs that mimicked the function and form of organic structures.

For example, Kurokawa designed towers in the shape of the DNA double helix, with elevators contained in the tubular spirals. Arata Isozaki, meanwhile, dreamed up the "Arai House," a 4.8-meter diameter sphere sheathed in a thin, flexible membrane that flooded the interior with diffused light.

Kenji Ekuan, who later went on to found the furniture company GK, took his inspiration from plants, imagining a "Chandelier City" in which cell-like polyhedrons dangled from stalks rooted in the ground.

While many of these designs seem straight out of science fiction, they were actually quite practical and borrowed heavily from traditional Japanese architecture.

For example, aggregative buildings such as Kurokawa's Nakagin, which is comprised of discrete "capsules" to be added or removed at will, were inspired by the modular system of tatami mats and sliding doors in traditional Japanese houses that allow for endless room configurations.

In Metabolism, these traditional aesthetics were merged with modern concerns: the movement's members were prescient in identifying the importance of renewable energy, with many of the large-scale developments powered entirely by solar or wave power units.

Japan's vulnerability to natural disasters was also carefully considered. For example, Kikutake's "Koto Project," a city of towers located on a grid of artificial ground in a sea-level district, was designed to be flood-proof.

The movement caught on quickly in Japan, with the World Design Conference in 1960 and the Osaka Expo in 1970 allowing Metabolist ideas to reach other countries.

Although some of their plans bewildered foreign architects--Kawazoe recalls one American calling Kikutake's plans "caricatures"--others were impressed and Metabolism's influence began to spread.

In 1968, Kikutake led a team of 20 architects to build a new kind of low-cost social housing in Peru at the behest of the Peruvian government and the United Nations. The houses they built are still standing, having been extended and altered by their inhabitants in accordance with the architects' wishes.

More recently, Kurokawa's plans for the world's first "ring city" were realized in 2004 in the central business district of Zhengdong, in Zhengzhou China. The circular development allows for a symbiotic relationship between nature and the city, with both skyscrapers and parks visible from all angles.

Tange, who was known for his ability to blend respect for tradition with modern design, has received countless commissions around the world, including rebuilding the capital of Macedonia, Skopje, after it was destroyed by an earthquake in 1963.

In Japan, Metabolism's legacy is even easier to see. The most obvious examples are those built by the central members of the group--for example, Tange's Meiji Jingu gymnasium in Harajuku, Tokyo, Sachio Otani's hexagonal Kyoto International Conference Hall, or Kurokawa's Yamagata's Hawaii Dreamland, based around looping circles.

The concentration of commerce around Japanese train stations today might have originated in the "Pear City Project," originally planned for the Denentoshi train line in Tokyo. The idea was to provide essential services locally, but also to encourage residents to travel beyond their immediate community for specialized or different services, in order to connect small communities and induce metabolic change in the surrounding area.

Whether a cause or effect of the movement, Japanese cities today "metabolize" extraordinarily quickly: The average building only stands for 20 years in Tokyo before being knocked down and replaced.

Even Nakagin, which was designed to be constantly updated and renewed, has fallen into the same trap. It is now uninhabited and destined for the demolition ball.

According to architect Kumiko Inui, speaking at a symposium held at the Shinkenchiku (New Architecture) headquarters in Tokyo on April 7 this year, Japanese cities "metabolize" because of weak land use legislation, leaving the nation ill-equipped to deal with natural disasters.

"Market-based land use inevitably tends to be biased toward the short term, (which makes) it is impossible to delegate preparations for disasters that occur only once over a span longer than a lifetime," Inui said. "(The March 11 earthquake) was a reminder of how important it is to take a long-term viewpoint in city planning."

However, it's not clear whether this slash-and-burn model of construction is what the Metabolists would have wanted.

As Masato Otaka and Fumihiko Maki first emphasized in a manifesto in 1960, Metabolism was based around the idea of "group form," where buildings should work together like a village, rather than being separate, isolated blocks.

As such, most of the Metabolists' plans were initially "top down," due to their complexity, but after being built they became "bottom-up," with residents left to decide how they should be adapted. Settlements were supposed to survive as a whole, while smaller parts might be replaced in accordance with the desires and needs of inhabitants.

With regards to reconstructing Tohoku, many have suggested moving residential areas further inland or to higher ground while leaving the marine industry on the coast. The Metabolists put forward similar zoning plans in their own plans, linking houses to schools, shops and workplaces with a transport network that echoed arterial systems, delivering people in the most efficient way possible.

Although many of their plans were never realized, and the failure of Nakagin shows that most people are not ready to live inside cell-like pods, modern architects still have much to learn from Metabolism.

In particular, the emphasis on empowering residents on a local level while providing a long term disaster-proof and self-sufficient framework on a macro level could prove useful to Tohoku. After all, what better way to protect against nature than to mimic it?

Yet, although most structures near the northeast coastline of Japan withstood the violent rumblings of the Great East Japan Earthquake, many did not survive the devastating power of the subsequent tsunami. As people wonder what would happen if a similarly large wave hit again, faith in Japan's model for urban planning and construction has been deeply shaken.

The architects in charge of reconstructing the Tohoku region must now not only plan disaster-resistant and energy-efficient settlements, but also find a way to serve the needs of the existing community as well as enticing others to move in and revitalize what was already an ailing region.

To do so, they might find some inspiration in the Metabolism school of architecture, which emerged during Japan's last large-scale reconstruction project in the postwar period. The movement is currently being explored in an exhibition at the Mori Art Museum in Roppongi, Tokyo, through Jan. 15.

Like the architects currently working on projects in Tohoku, the Metabolists were faced with the challenge of rebuilding from scratch. They determined that traditional urban models, comprised of clusters of discrete buildings, were not up to the task. Instead, they envisioned self-regulatory, cooperative and integrated structures that functioned like an ant colony or cells and organic systems of the human body.

According to architecture critic Noboru Kawazoe, the central members of the movement--which included Kenzo Tange, Kisho Kurokawa and Kiyonori Kikutake--believed that buildings and settlements should grow and adapt to their environment, letting the old be replaced by the new. In nature this process is known as "metabolism," hence the name of the movement.

"Life forms are different from everything else because they keep growing as they are replaced," Kawazoe said. "Humans are just another life form on earth--and the cities we build are just the same as anthills."

Taking their inspiration from cells, honeycombs and fractals, the Metabolists produced dazzlingly futuristic designs that mimicked the function and form of organic structures.

For example, Kurokawa designed towers in the shape of the DNA double helix, with elevators contained in the tubular spirals. Arata Isozaki, meanwhile, dreamed up the "Arai House," a 4.8-meter diameter sphere sheathed in a thin, flexible membrane that flooded the interior with diffused light.

Kenji Ekuan, who later went on to found the furniture company GK, took his inspiration from plants, imagining a "Chandelier City" in which cell-like polyhedrons dangled from stalks rooted in the ground.

While many of these designs seem straight out of science fiction, they were actually quite practical and borrowed heavily from traditional Japanese architecture.

For example, aggregative buildings such as Kurokawa's Nakagin, which is comprised of discrete "capsules" to be added or removed at will, were inspired by the modular system of tatami mats and sliding doors in traditional Japanese houses that allow for endless room configurations.

In Metabolism, these traditional aesthetics were merged with modern concerns: the movement's members were prescient in identifying the importance of renewable energy, with many of the large-scale developments powered entirely by solar or wave power units.

Japan's vulnerability to natural disasters was also carefully considered. For example, Kikutake's "Koto Project," a city of towers located on a grid of artificial ground in a sea-level district, was designed to be flood-proof.

The movement caught on quickly in Japan, with the World Design Conference in 1960 and the Osaka Expo in 1970 allowing Metabolist ideas to reach other countries.

Although some of their plans bewildered foreign architects--Kawazoe recalls one American calling Kikutake's plans "caricatures"--others were impressed and Metabolism's influence began to spread.

In 1968, Kikutake led a team of 20 architects to build a new kind of low-cost social housing in Peru at the behest of the Peruvian government and the United Nations. The houses they built are still standing, having been extended and altered by their inhabitants in accordance with the architects' wishes.

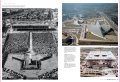

More recently, Kurokawa's plans for the world's first "ring city" were realized in 2004 in the central business district of Zhengdong, in Zhengzhou China. The circular development allows for a symbiotic relationship between nature and the city, with both skyscrapers and parks visible from all angles.

Tange, who was known for his ability to blend respect for tradition with modern design, has received countless commissions around the world, including rebuilding the capital of Macedonia, Skopje, after it was destroyed by an earthquake in 1963.

In Japan, Metabolism's legacy is even easier to see. The most obvious examples are those built by the central members of the group--for example, Tange's Meiji Jingu gymnasium in Harajuku, Tokyo, Sachio Otani's hexagonal Kyoto International Conference Hall, or Kurokawa's Yamagata's Hawaii Dreamland, based around looping circles.

The concentration of commerce around Japanese train stations today might have originated in the "Pear City Project," originally planned for the Denentoshi train line in Tokyo. The idea was to provide essential services locally, but also to encourage residents to travel beyond their immediate community for specialized or different services, in order to connect small communities and induce metabolic change in the surrounding area.

Whether a cause or effect of the movement, Japanese cities today "metabolize" extraordinarily quickly: The average building only stands for 20 years in Tokyo before being knocked down and replaced.

Even Nakagin, which was designed to be constantly updated and renewed, has fallen into the same trap. It is now uninhabited and destined for the demolition ball.

According to architect Kumiko Inui, speaking at a symposium held at the Shinkenchiku (New Architecture) headquarters in Tokyo on April 7 this year, Japanese cities "metabolize" because of weak land use legislation, leaving the nation ill-equipped to deal with natural disasters.

"Market-based land use inevitably tends to be biased toward the short term, (which makes) it is impossible to delegate preparations for disasters that occur only once over a span longer than a lifetime," Inui said. "(The March 11 earthquake) was a reminder of how important it is to take a long-term viewpoint in city planning."

However, it's not clear whether this slash-and-burn model of construction is what the Metabolists would have wanted.

As Masato Otaka and Fumihiko Maki first emphasized in a manifesto in 1960, Metabolism was based around the idea of "group form," where buildings should work together like a village, rather than being separate, isolated blocks.

As such, most of the Metabolists' plans were initially "top down," due to their complexity, but after being built they became "bottom-up," with residents left to decide how they should be adapted. Settlements were supposed to survive as a whole, while smaller parts might be replaced in accordance with the desires and needs of inhabitants.

With regards to reconstructing Tohoku, many have suggested moving residential areas further inland or to higher ground while leaving the marine industry on the coast. The Metabolists put forward similar zoning plans in their own plans, linking houses to schools, shops and workplaces with a transport network that echoed arterial systems, delivering people in the most efficient way possible.

Although many of their plans were never realized, and the failure of Nakagin shows that most people are not ready to live inside cell-like pods, modern architects still have much to learn from Metabolism.

In particular, the emphasis on empowering residents on a local level while providing a long term disaster-proof and self-sufficient framework on a macro level could prove useful to Tohoku. After all, what better way to protect against nature than to mimic it?

Project Japan, Metabolism Talks…

Back to the future

Visionary architecture in postwar Japan

“Once there was a nation that went to war, but after they conquered a continent their own country was destroyed by atom bombs... then the victors imposed democracy on the vanquished. For a group of apprentice architects, artists, and designers, led by a visionary, the dire situation of their country was not an obstacle but an inspiration to plan and think… although they were very different characters, the architects worked closely together to realize their dreams, staunchly supported by a super-creative bureaucracy and an activist state... after 15 years of incubation, they surprised the world with a new architecture—Metabolism—that proposed a radical makeover of the entire land... Then newspapers, magazines, and TV turned the architects into heroes: thinkers and doers, thoroughly modern men… Through sheer hard work, discipline, and the integration of all forms of creativity, their country, Japan, became a shining example... when the oil crisis initiated the end of the West, the architects of Japan spread out over the world to define the contours of a post-Western aesthetic....” —Rem Koolhaas / Hans Ulrich Obrist

Between 2005 and 2011, architect Rem Koolhaas and curator Hans Ulrich Obrist interviewed the surviving members of Metabolism—the first non-western avant-garde, launched in Tokyo in 1960, in the midst of Japan’s postwar miracle. Project Japan features hundreds of never-before-seen images—master plans from Manchuria to Tokyo, intimate snapshots of the Metabolists at work and play, architectural models, magazine excerpts, and astonishing sci-fi urban visions—telling the 20th century history of Japan through its architecture, from the tabula rasa of a colonized Manchuria in the 1930s to a devastated Japan after the war, the establishment of Metabolism at the 1960 World Design Conference in Tokoy, to the rise of Kisho Kurokawa as the first celebrity architect, to the apotheosis of Metabolism at Expo ’70 in Osaka and its expansion into the Middle East and Africa in the 1970s. The result is a vivid documentary of the last moment when architecture was a public rather than a private affair.

* Oral history by Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist

* Extensive interviews with Arata Isozaki, Toshiko Kato, Kiyonori Kikutake, Noboru Kawazoe, Fumihiko Maki, Kisho Kurokawa, Kenji Ekuan, Atsushi Shimokobe, and Takako and Noritaka Tange

* Hundreds of never-before-seen images, architectural models, and magazine excerpts

Exhibition Mori Museum, Tokyo

Further reading

The editors and authors:

Rem Koolhaas is a co-founder of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture. Having worked as a journalist and script writer before becoming an architect, in 1978 he published Delirious New York. In 1995, his book S,M,L,XL summarized the work of OMA and established connections of contemporary society and architecture. Amongst many international awards and exhibitions he received the Pritzker Prize (2000) and the Praemium Imperiale (2003).

Hans Ulrich Obrist (born 1968) is a curator, critic and historian. He is currently Co-director of Exhibitions and Programmes and Director of International Projects at the Serpentine Gallery, London. Obrist is the author of The Interview Project, an extensive ongoing project of interviews.

沒有留言:

張貼留言